An album is bigger than the moments in which it was almost halted from being, and Sticky Fingers is a doozy. Ultimately, the obstacles The Rolling Stones overcame to conjure the blues-magic of one of their most enduring works boil down to the same hurdles that obstruct most of everything: money and death.

By the end of their first decade of prominence The Rolling Stones had become more symbolic of the biblical trifecta (Sex, Drugs, Rock ‘n Roll) than any of their contemporaries, before or after. The Sex is self-explanatory; read through the lyrics of any of their albums, and be struck by Jagger’s tantric side with all the subtlety of an NFL linebacker blitzing a quarterback. The Drugs were a bit murkier. The peak (or nadir, depending on your perspective) of the Stones' affair with illicit substances occurred in 1967, at Keith Richard's Sussex home Redlands, West Wittering, when the police raided the estate as Richards, Mick Jagger and Jagger’s then-girlfriend Marianne Faithfull were coming down from an acid trip. Richards spent a seemingly nonchalant night in jail, saying “The judge managed to turn me into some folk hero overnight. I've been playing up to it ever since.”

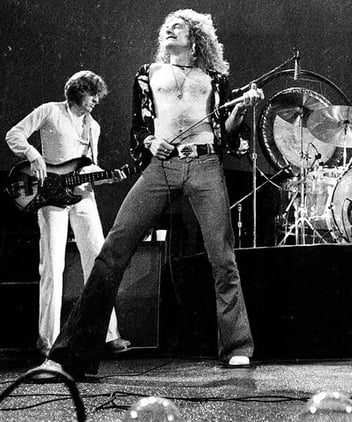

So the Rock ‘n Roll was far from murky. It shone as bright as a polished belt buckle. By March 1969, by which point they had already released Beggar’s Banquet, and Let It Bleed, they had done as much as anyone to define what we consider Rock and Roll. Zeppelin had veered into their own territory. The Beatles kept getting weirder (and fighting), but the Rolling Stones had it in their name. They embodied the philosophy, and the unwholesomeness of their late-60s reign proved they lived the lifestyle. As much as the music, their ventures defined their legend.

Despite touching down in the thick of their legendary four-album run — Exile On Main St. following — Sticky Fingers was released at one of the lowest points in the Stones' career. They were broke, and people were dying around them.

Emerging from their contract with Decca Records — after submitting Cocksucker Blues, their final obligation — the Stones launched Rolling Stones Records as a vehicle to complete artistic freedom and ownership of their property, which was a great idea. At the time, labels and their suits routinely concocted absurd clauses to take advantage of their artists to maintain control of their music and distribution, effectively drying out their income. A good example of this is Allen Klein of ABKCO Music & Records, a talent manager who set up label deposits into his own company and structured contracts so as to command distribution of royalties, publishing rights, and tax autonomy. He happened to be introduced to the Stones in 1965, and by the time recording for Sticky Fingers had begun, he had suffocated them. So Rolling Stones Records was off to a penniless start. But at least they had their freedom.

As for the death: there were three pronounced losses in the lead-up to Sticky Fingers — the mortal losses of Brian Jones and Meredith Hunter, and the existential death of the 60’s peace ‘n luv era.

By the time they had begun recording Let It Bleed in 1969, The Stones had leaned out from a quintet to a foursome, dropping founding slide-guitarist Brian Jones from the official roster due to his worsening addiction issues and subsequent lack of dependability. Jones would be found a couple of months later at the bottom of his pool, having drowned himself during a binge. His ghost would haunt much of Sticky Fingers’ recording.

Meredith Hunter was an eighteen-year-old from Berkley, California who travelled with his girlfriend to see the Stones at the Altamont Free Concert, a one-day music festival on December 6, 1969, at the Altamont Speedway, where 300,000 fans expected a West Coast answer to New York’s Woodstock prior that year. The Rolling Stones closed out the evening, following an all-star lineup of Santana, Jefferson Airplane, The Flying Burrito Brothers and CSNY. The Grateful Dead were scheduled to perform but dropped out citing unease at the loose organization of the festival and potential for catastrophe, namely the lack of facilities like toilets and medical stations, the risky placement of a meter-high stage at the bottom of a slope, and that security was provided by the Hell’s Angels in exchange for $500-worth of beer (equivalent to $4,445 in 2025). The drunken Angel’s were reported to have used motorcycle chains and pool cues to keep the agitated crowd at bay. Hunter, after being assaulted by ‘security,’ pulled a firearm, raised the firearm, and was promptly disarmed, stabbed and beaten to death. Another man fell down an irrigation system while high on acid, drowning. Three more were killed in a hit-and-run at the Speedway’s gate. It’s been referred to as the darkest in Rock and Roll history, and the day the youthful altruism of the 60’s hippie movement came to a bloody close. Richards, at the time unaware of the deaths, was able to avoid any molestation himself, saying “A few tempers were frayed [...] on the whole, a good concert.”

But death is a revolving door, and in the loss of their past, the Stones found new life. Rolling Stones Records did indeed liftoff. Mick Taylor, who had filled in for Jones on Let It Bleed, and became a full-time member to record Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, refreshed the group, breathing new air into their country-tinged blues rock. Sticky Fingers galvanized the uninhibited energy of their tenure as Rock’s — and, truly, the world’s — foremost bad boys. It’s arguably the darkest record in their catalogue, a return to their dirty, unhinged early years. It peaked on every national chart save Italy and Japan (where it came 5th and 9th, respectively). Its iconic cover of an anonymous pair of hips was released with a real zipper that infamously damaged neighbouring vinyl records. It was the debut of the tongue and lips, the most famous logo in music history.

By all accounts, Sticky Fingers should have been a failure, an understandable collapse by a band that should have unravelled. No one would have blamed them if, considering what they had already accomplished, they dropped a stinker. And yet, from the deepest valley of their careers thus far, the Rolling Stones dug deep and excavated a crown gem. Over a half-century later, Sticky Fingers still stands among the highest points in one of Rock and Roll’s most soaring legacies.

Want to hear Sticky Fingers like never before? Join Arts Commons Presents and Classic Albums Live on May 3rd for an authentic note-for-note recreation of the album –– plus The Stones' greatest hits –– live onstage.

Thomas Johnson

Thomas Johnson is the tallest rap critic in Calgary. His work has yet to appear in the Louvre. You can find him listening to all sorts of everything at Blackbyrd Myoozik.