It's very likely that in just this year, you’ve probably seen one of these headlines:

“The Russians/Chinese/Americans are coming for our Arctic”, “Canadian Sovereignty at Risk in the Arctic”, or “The Arctic is Canada’s undefended front.”

If you stick around past the headlines, articles on Canada’s Arctic are full of calls to action from politicians, pundits, and citizens. Calls to build naval bases, airfields, and more soldiers. Ice breakers, naval bases, soldiers, and fighter jets have been at the top of the list for politicians from both Liberal and Conservative platforms when addressing “securing” the Arctic.

What is sadly quite common –– and what is missing with many of these pieces –– is the perspective and needs of those who call one of the most beautifully hostile regions in the world home. We have not stopped to listen, let alone ask.

There is a shared experience with all Canadian Indigenous people, where decisions that impact our lives and communities were made by those who don’t understand or want to understand what it means to call the land home. Truth and Reconciliation pointed out the colonial hypocrisy of thinking European ways could be implemented without the consent of Indigenous people. In the cities and provinces of Canada below the 60th parallel, TRC is a reality of life now, with colonial generalizations and paternalistic thinking a thing of the past.

Yet it still seems ok to do so about the Arctic.

To watch people who have never spent a night under the northern lights, never felt the cold on their cheeks, or the awe of isolation on the tundra, speak on behalf of the Arctic is insulting at best. Sweeping generalizations of a richly diverse people and terrain preceding solutions to a changing Arctic that are functionally, logistically, socially, and culturally incompatible with the north are commonplace. It is at best frustrating and at worst infuriating. I know this, because I have had the privilege of listening to many of their stories firsthand on their land.

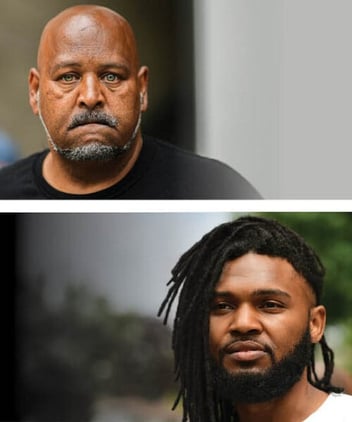

I have had the honour of working in the Arctic as a journalist, covering topics and events on Arctic security for the past several years. From Resolute to Tuktoyaktuk, my work has brought me to know many of the Canadian Rangers, a distinct and unique group in the Canadian Army tasked with being the “eyes and ears” of the north. However, I now firmly believe they make up an important part of its voice.

Photojournalist Gavin John pictured in the Arctic.

I have never claimed to be a northerner nor someone who, despite my own Indigeneity, has never claimed to know what it means to be Indigenous to the north. The diverse nations, communities, and traditional land of the Inuit, Gwitch’in, Dene, and other Indigenous groups are all worthy of time to listen and understand.

Listening, observing, and learning are already part of good journalism, and the more time I spent with the many people of the north the more it became clear that subtly had purpose. Material that gloves and parkas were made of became symbols of home, lifestyle, and utility and reading the snow to know the weather or tell direction is an art form. It’s one thing to be told Traditional Knowledge, but to experience it alongside practitioners is another level.

I’ve travelled above the Arctic Circle three times in the past year alone. In the middle of summer, to the depths of winter, on snowmobile and by air force reconnaissance planes, from -50 to +30, I’ve still seen just a fraction of what the Arctic has to share –– all under the kind and watchful eyes of the Rangers.

Whether it has been 130km snowmobile patrol down the Mackenzie River with Rangers from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk or listening to stories of summer on the tundra while camped out on the Northwest Passage, there is wisdom to learn on every one of my visits. In July, I will be travelling the furthest north I have ever and will likely ever be, to the northern edges of Ellesmere Island with the Rangers.

However, if there is one thing that I have learned by being welcomed by many from the Arctic, is that they have valuable insights and pragmatic solutions to the daunting problems of Arctic security.

Paved runways for communities bring not only lower costs of living for residents, but also the ability to land jets, drones, and military transport planes. Developed commercial ports and increased warehouse space increase self-sufficiency and economic prosperity for communities. Greater economic prosperity means Rangers do not have to choose between deploying on patrols or working multiple jobs to make a living. More Rangers on the land means a light footprint presence that they excel at, providing a balance of environmental protection and military presence. This was explained to me by an Inuit Ranger over caribou stew along the Mackenzie River this past February. Arctic problems must have solutions with buy-in from Arctic inhabitants, not just token consultation or checkboxes.

To share stories with one another requires trust, and trust requires time. My work in the Arctic will continue for years to come, and the stories of the people from the Canadian Rangers will likely not be ready anytime soon. I am excited to share my experiences and understandings with Canadians, but only when it is ready and only when the voices I share are properly represented.

I am not from the North, nor will I ever claim to be. Yet, the North has me captivated and I have a continuing obligation to listen, learn, and share from those who live there.

Before Canada can help the North, we need to listen to the North.

Gavin John is now a New York Times published journalist! Check out his piece "Patrolling the High Arctic, Rifles and Snow Shoes at the Ready."

All photos by Gavin John

Interested in hearing more from Gavin John and other local artists? Head over to our friends at The Scene and discover more great interviews, artist features, and highlights from Calgary’s arts and culture scene.

Gavin John

Gavin John is a documentary photographer and photojournalist based in Calgary, Canada. Gavin’s work focuses on documenting conflict, unrest, and social issues. His work has taken him to document events in Iraq, North Korea, the United States, the Philippines, and around Canada. Gavin is a proud member of Indigenous Photograph collective.